Genome organisation in eukaryotes is like a well-arranged library, where every “book” of DNA has a proper place, structure, and function inside the nucleus. Imagine thousands of long scrolls (the DNA molecules) carefully wound around spools (histone proteins) to form neat packages (nucleosomes), then stacked into shelves (chromatin fibres), and finally organised into distinct sections (chromosomes) within a secure reading room (the nucleus).

Without this structured approach, the DNA would tangle and become unusable, much like books scattered randomly across a library floor. This elegant packing explains why eukaryotic cells, despite their larger size of typical eukaryotic cell (10-100 µm), can manage complex functions that prokaryotes cannot.

Our blog explains genome organisation, compares it with genome organisation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and links it to the types of eukaryotic cells and the size of typical eukaryotic cell.

Why study genome organisation?

“DNA is like a script, but genome organisation decides how the story is read.”

This idea captures why genome organisation matters so much in biology and medicine. When students ask, “What is the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleus?” or “How does cell size affect DNA packing?”, they are indirectly asking about genome organisation.

In simple terms, genome organisation means how DNA is arranged, packed, and controlled inside the cell. Understanding genome organisation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes helps relate bacteria, plants, animals, and humans on one clear framework.

Basics: Eukaryotic cells and their genome

Let’s explore the types of eukaryotic cells and their basic features.

- Animal cells: No cell wall, have centrioles, many types like muscle cells, nerve cells, blood cells.

- Plant cells: Have cell wall, chloroplasts, large vacuole.

- Fungal and protist cells: Eukaryotic but with their own special structures.

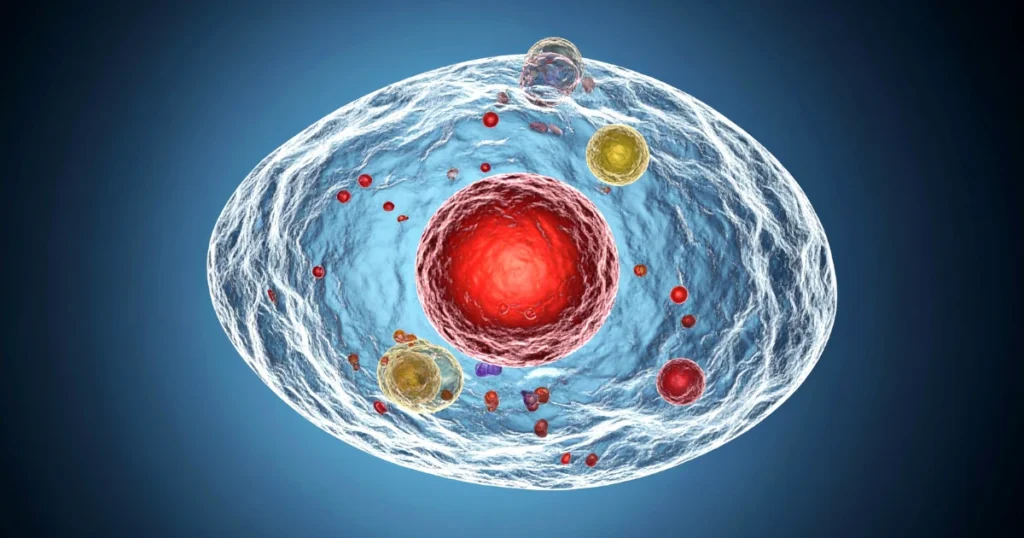

Across these types of eukaryotic cells, one common point is a well-defined nucleus that holds the DNA as linear chromosomes. The size of typical eukaryotic cell usually ranges from about 10 to 100 micrometres in diameter, which is much larger than prokaryotic cells.

“The total length of DNA in a human cell is nearly 2 metres, but it fits inside a nucleus of only about 5–10 µm.”

This famous example clearly shows why genome organisation must be highly structured and efficient.

Read More: How Genome Sequencing Can Predict Your Future Health

Prokaryotic vs Eukaryotic Nucleus: Differences

When you ask what is the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleus, you are really comparing two styles of genome organisation.

- Prokaryotic cells (like bacteria):

- No true nucleus; DNA is in a nucleoid region.

- DNA is usually a single circular chromosome, often with plasmids.

- Eukaryotic cells:

- Have a membrane-bound nucleus.

- DNA is arranged in multiple linear chromosomes with histone proteins.

So, what is the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleus? In short, prokaryotes have an open nucleoid without a nuclear membrane, while eukaryotes have a distinct nucleus with tightly packaged chromatin. This distinction is central when comparing genome organisation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Levels Of Genome Organisation In Eukaryotes

Now let us look step by step at how the genome organisation happens from DNA to chromosomes.

1. DNA and histones: forming nucleosomes

Inside the nucleus, DNA does not float loosely. It wraps around proteins called histones to form nucleosomes.

- A nucleosome has about 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of histones (H2A, H2B, H3, H4).

- This looks like “beads on a string” under the microscope.

This is the first level of genome organisation, where long DNA becomes compact, but still accessible for gene expression.

2. Chromatin fibres and higher-order folding

Nucleosomes further fold into a 30 nm chromatin fibre, with help from linker histone H1 and other proteins.

- These fibres then form loops and domains attached to a nuclear scaffold.

- Loops bring distant genes and regulatory elements (like enhancers and promoters) close together, affecting gene activity.

At this level, genome organisation in eukaryotes becomes three-dimensional, not just a simple linear chain of genes.

3. Euchromatin and heterochromatin

Chromatin is not uniform; it has two main functional forms.

- Euchromatin: Loosely packed, gene-rich, and usually active in transcription.

- Heterochromatin: Densely packed, often gene-poor or silent, includes centromeres and telomeres.

So, genome organisation is dynamic. Parts of the genome can open or close depending on cell type and signals, which links to the types of eukaryotic cells and their specialised functions.

4. Chromosomes in the nucleus

All this folding finally leads to visible chromosomes during cell division.

- Each eukaryotic chromosome contains a single long DNA molecule plus associated protein.

- Different species have different chromosome numbers, but the basic structure is similar.

This shows how the large DNA content is managed inside the limited size of typical eukaryotic cell and its small nucleus.

Genome Organisation in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

To make genome organisation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes clearer, here is a short comparison.

| Features | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes |

| Genome shape | Mostly circular DNA | Linear DNA in chromosomes |

| Nucleus | No true nucleus (nucleoid) | Membrane-bound nucleus |

| Histones | Generally absent | DNA wrapped around histones, forms chromatin |

| Gene organisation | Often in operons, high gene density | Genes with introns, more non-coding DNA |

| Cell size | About 0.1–5 µm | Size of typical eukaryotic cell is 10–100 µm |

This table answers not only what is the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleus, but also how that affects entire genome organisation.

Cell Size and Genome Organisation

You may wonder: how does the size of typical eukaryotic cell relate to genome organisation?

- Eukaryotic cells (10–100 µm) are much larger than prokaryotic cells (0.1–5 µm), and they contain more DNA.

- Because of this, multi-level packing into nucleosomes, chromatin fibres, and chromosomes is essential.

As aforementioned, eukaryotic cells are much larger than prokaryotic cells and they contain more DNA, often thousands of times more genetic material. Because of this, multi-level packing into nucleosomes, chromatin fibres, and chromosomes is essential to fit everything inside the nucleus while keeping genes accessible.

The size of typical eukaryotic cell also varies among the types of eukaryotic cells, for example, small blood cells (about 7–10 µm), large plant cells (up to 100 µm with vacuoles), or long nerve cells (over 1 metre in length but only 10 µm wide). Yet the principle remains similar across all: DNA wraps around histones regardless of cell shape or function.

Why does size matter for genome function?

- Larger cells need more efficient gene regulation to coordinate complex activities (like neuron signalling vs bacterial division).

- The nucleus scales with cell size, but packing ratios stay consistent, about 10,000-fold DNA compaction.

- This relates directly to what is the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleus: prokaryotes pack simply because their small size allows direct DNA access, while eukaryotes evolved elaborate systems for their bigger, specialised types of eukaryotic cells.

Why genome organisation matters?

Genome organisation is not just about fitting DNA into a small space. It directly affects:

- Which genes are active in different types of eukaryotic cells (for example, liver vs neuron).

- How quickly a cell can respond to signals by turning genes on or off.

- How stable the genome remains across cell divisions.

So, when biologists analyse genome organisation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, they also study how structure drives function and health.

Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) Connection

The Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) plays a key role in mapping genome organisation, especially the human genome.

Launched in 1989, HUGO coordinates global efforts to sequence, analyse, and standardise human genetic data. Its work reveals how our linear chromosomes, chromatin structures, and gene regulation follow the same genome organisation principles discussed earlier, histone packing, euchromatin/heterochromatin states, and nuclear organisation.

Major HUGO contributions:

- Standardised human gene nomenclature (e.g., naming genes like TP53)

- Created genome browsers showing chromatin domains and regulatory elements

- Supports research comparing genome organisation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes through model organisms

Today, HUGO’s databases help researchers understand how the size of typical eukaryotic cell (like human cells at 10–30 µm) manages 3 billion DNA base pairs across 23 chromosome pairs. This directly applies what is the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleus to human health and disease research.

On A Final Note…

Genome organisation shines a light on the nature’s clever design for managing vast genetic information within the limited space of a cell nucleus. From nucleosomes to chromatin loops and chromosomes, this structured packing not only fits 2 metres of DNA into a 10 µm nucleus but also controls which genes activate in different types of eukaryotic cells.

This knowledge forms the foundation for fields like genetic engineering, cancer research, and biotechnology in India, where genome studies drive medical innovation.

FAQs

1. What is genome organisation in eukaryotes?

DNA packed with histones into nucleosomes, chromatin, and chromosomes inside a nucleus.

2. What is the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic nucleus?

Prokaryotes: no membrane, circular DNA in nucleoid. Eukaryotes: membrane-bound with linear chromosomes.

3. Size of typical eukaryotic cell?

10–100 micrometres in diameter.

4. Genome organisation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes?

Prokaryotes: circular, no histones. Eukaryotes: linear, histone-packed chromatin.

5. Types of eukaryotic cells and genome?

Animal, plant, fungi, protists, all use same genome packing but activate different genes.